Project

Why Slow Motion?

Slow motion is widely employed in popular media such as emotional movie scenes or in the broadcasting of momentous bodily and physical actions. Slow motion offers new aesthetic experiences and intriguing insights in music, dance and sport genres. While it is used as a beneficial rehearsal strategy in music, slow movements are more constrained by the need for momentum in dance and sports. Slowing down may also function as a counterpoint to the perceived acceleration of life, with various initiatives and meditation practices promoting benefits for health and wellbeing.

We argue that music, as a temporal-motional art, is central to understand the appeal and effects of slow motion and slow movements. Music consists of structured time at different hierarchical levels and deeply “moves” people – it may allow the passing of time in new terms. Super-slowness, at the furthest end of the spectrum, may involve temporal events that are too slow for human perception. Since music is multimodal at its core, involving motor, visual and auditory systems in performance, perception and imagination, strong links to other movement-based practices exist. Thus new understandings of slowness are possible by investigating these sensory modalities and processes. While the discussion of slowness in different contexts grows, not much is known yet about its effect on motor skills, cognitive load, memory, emotion or imagination.

How do we work?

This EU-funded research investigates “stretched time” in the performance and perception of music and selected dance genres. Emphasis is placed on differences between mediated slow motion and performed slow movements.

In Phase A we investigate mediated and perceived slow motion. These studies address the structural levels of musical time and the audiovisual perception of movement speed. We analyse the effects on attention, cognitive load and emotional and aesthetic responses to music and dance in relation to tempo and playback speed, including super slow motion.

Phase B analyses movement characteristics and psychological processes of moving slowly in performance. For instance, we study the imagery and affective states of dancers and musicians, including effects on agency as well as slow ensemble synchronisation.

Phase C integrates the outcomes of the first two phases and uses material from the research studies. This should inspire creative responses for performance, rehearsal and aesthetic involvement, and stimulate further empirical research.

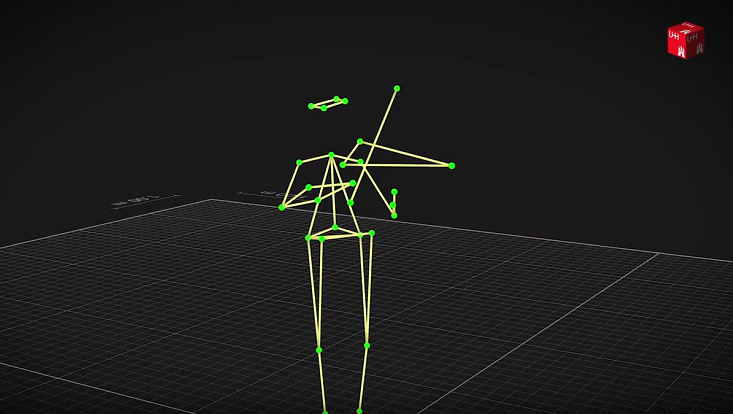

The SloMo project, which started in April 2017 for a duration of five years, combines approaches from a variety of disciplines including music psychology, cognitive psychology and dance and performance studies. State-of-the-art methods and technology are employed, including motion capture, eye tracking, high-speed video, and EMG (see SloMo Lab). We analyse field and lab recordings, using controlled experimental as well as ecologically valid designs, and we strongly aim for theory development.

What have we found so far?

So far, we have investigated a) slow motion in media, b) individuals’ time perception while tapping along with music and rhythmic patterns, c) motion capture of dance patterns at different speeds, c) the perception of slow motion in point-light displays, d) carried out a systematic review of inner clocks and time perception for audiovisual stimuli, e) tested audiovisually incongruent stimuli in a perception study, f) investigated the tempo anchoring effect (TAE) on the perceived duration and tempo of music, as well as g) the influence of tempo on dance movement, h) analysed factors influencing spontaneous motor tempo (SMT), and i) focus of attention in slow practice scenarios, as well as j) the performance and perception of professional drumming at different speeds.

Our research into the perception of commercial films, dance and sports footage has shown that slow motion leads to an underestimation of time and affects the physiological correlates of emotional responses. Using an eye tracking device, we also found that slow motion influences gaze behaviour, allowing for more attention to details in movies. Music modulates these processes strongly, for instance leading to larger pupil diameters as a measure of arousal.

In a study investigating the relation between sensorimotor synchronisation to different structural levels in music and time perception, we found that entrainment to higher structural levels shortens perceived duration. In a different study participants were asked to judge the passage of time while listening to examples of hip-hop music that varied in arousal but were constant in tempo. Participants judged the passage of time to be quicker when cognitive load was high in a dual-task condition (additional working memory task), and perceived duration to be shorter when performing a concurrent motor task (tapping along with the music).

For the purpose of examining motor control and movement consistency in the context of tempo, laterality, and music and dance expertise, participants were instructed to perform repetitive dance-like sequences. Maintaining velocity consistency was more challenging at slow tempi than at faster tempi. Music proficiency seems to affect consistency to a higher degree than dance proficiency, leading to potential implications for practicing and training in musical instruments, dance, and sports.

When participants were asked to watch point-light displays of themselves and another unknown person, results indicate that speed of movement affected duration estimations. This effect was stronger for watching others' movements, and duration estimations were longer after acting out the movement compared to watching it. Findings suggest that aspects of temporal processing of visual stimuli may be modulated by inner motor representations of previously performed movements, and by physically carrying out an action compared to just watching it. Results also support inner clock theories of time perception for the processing of human motion stimuli, which can inform the temporal mechanisms of a hypothesised separate working memory processor for human movement information.

Multiple studies have shown that music may lead to new experiences of time based on the listeners’ focus of attention. Taken together, these findings indicate consistent effects of attention and cognitive load on time experiences. Regarding the underlying cognitive processes, a major endeavour has been reviewing established internal clock models, and their explanatory power in audiovisual perception. In a series of studies we investigated effects of attentional focus on motor tasks and slow musical practice. An online survey showed that slow practice is a widely used technique serving expressive, technical, and preparatory functions – providing groundwork for further research into tempo-regulated training strategies.

Since temporal processing depends on auditory, as well as visual information, we further investigated participants' tempo judgments when they were presented with audiovisual stimuli with various degrees of congruence. In the fast tempo range, participants tended to judge “fast” significantly more often with visual cues regardless of the auditory tempo, whereas in the slow range, they did significantly less often so. This revealed a higher reliance on visual tempo compared to the auditory tempo in overall tempo judgments.

Spontaneous motor tempo (SMT) can be regarded as an estimate of the internal clock and is closely related to the preferred perceived tempo in music as well. Two studies investigated factors influencing its pace. In a large-scale online study, we were able to show that the SMT is not only affected by age (higher age slows down the SMT) and arousal (higher arousal levels speed up the SMT) but als by the time of the day (slower SMT in the morning). This finding was further investigated in a second study using an experience sampling method, measuring participants’ SMT four times a day over the course of a week. The study confirmed the arousal and time of the day effects further showing that the SMT does not only change during the day but this change depends on someone’s chronotype.

Continuing the investigation of audiovisual movement information, we recorded several professional breakdancers with highspeed cameras. The resulting slow motion footage will be used for additional tempo perception studies.

Project SloMo in the media

Hamburg - Metropole des Wissens: Overview of the SloMo project

The Strad - Why 10,000 hours of practice won't make you an expert

Universität Hamburg 19neunzehn Magazine: Die Macht der Musik

Universität Hamburg - News article about the 'Time changes...' symposium